Unearthing the Sheikh el-Balad

In the sun-baked sands of Saqqara, a remarkable discovery was made that would captivate the world of Egyptology. As French archaeologist Auguste Mariette’s team toiled under the scorching Egyptian sun, they unearthed a wooden statue so lifelike that it earned an unexpected nickname.

A Chief Among Priests

The statue depicted Kaaper, a chief lector priest whose sacred duty was to recite prayers for the deceased in temples and funerary chapels. But it wasn’t just Kaaper’s role that made this discovery extraordinary. The workmen, struck by the statue’s uncanny resemblance to their own village chief, christened it “Sheikh el-Balad” – the Arabic title for the chief of the village.

A Masterpiece of Old Kingdom Craftsmanship

Wood: The Medium of Masters

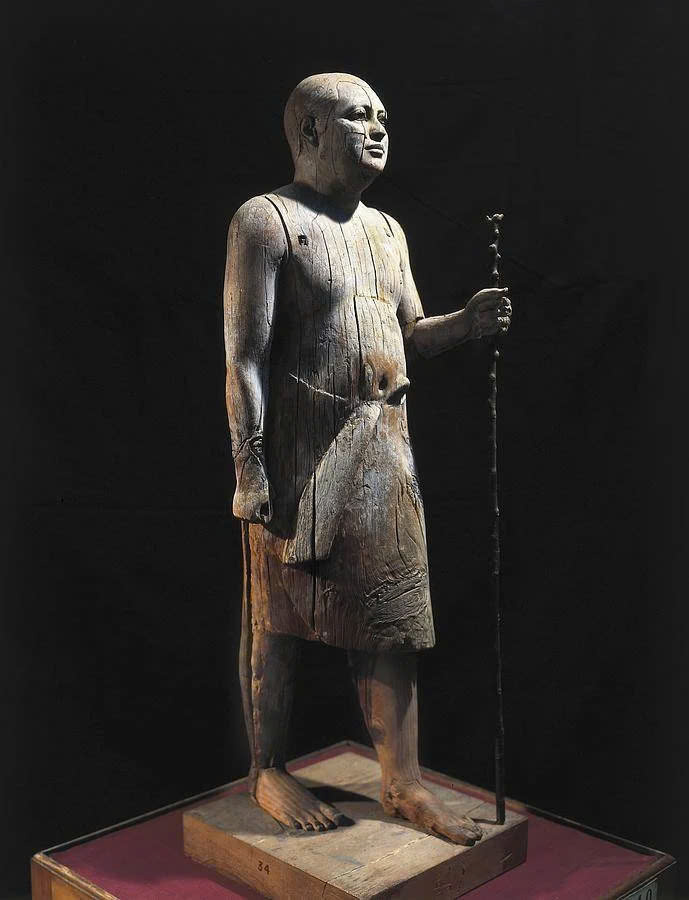

Dating back to the 5th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom (ca. 2494-2345 BC), this 112 cm tall sycamore statue represents a pinnacle of ancient Egyptian woodworking. The use of wood in sculpture had become more established during the 4th Dynasty, offering greater versatility than stone, albeit at the cost of durability. The survival of Kaaper’s statue is a rare gift from the past, escaping the ravages of time that claimed so many of its contemporaries.

Bringing Wood to Life

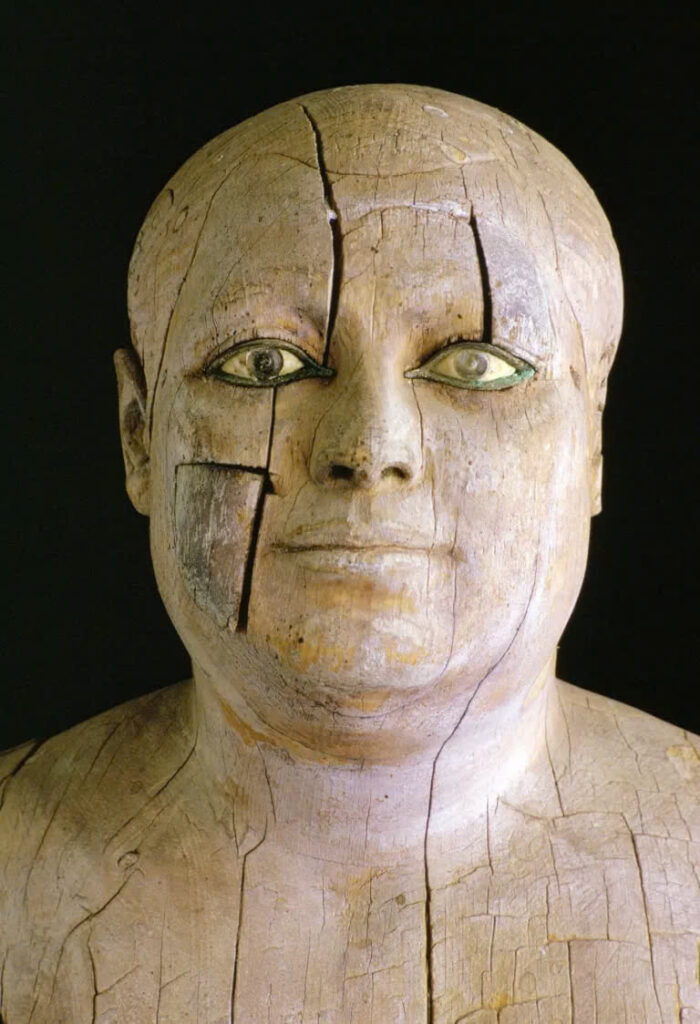

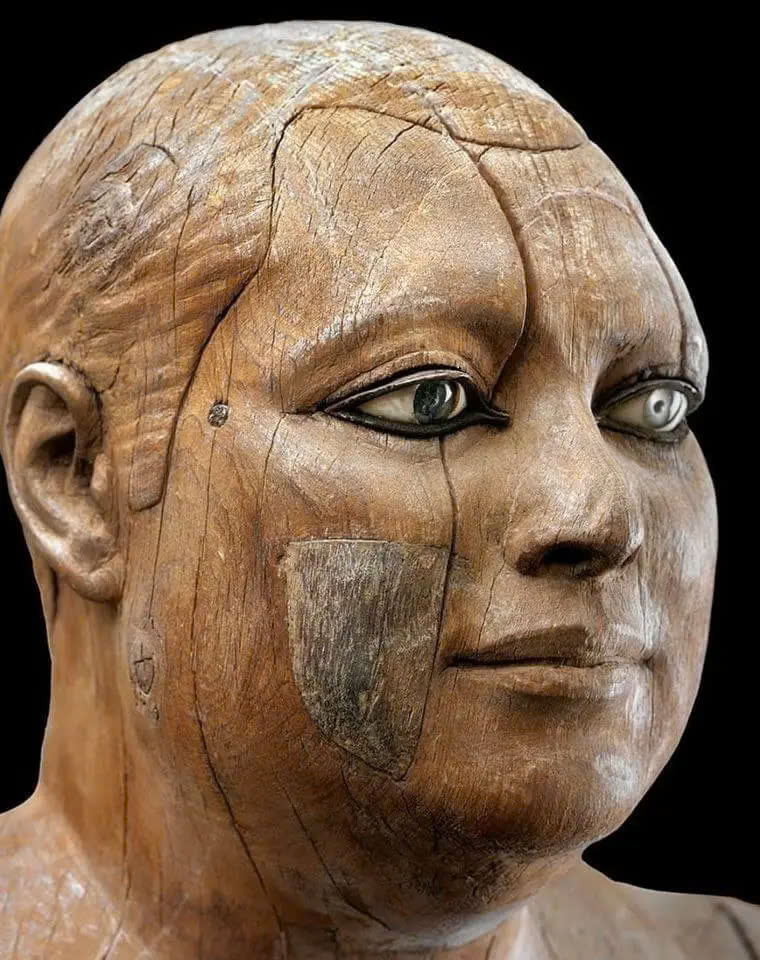

The statue’s realism is breathtaking. Kaaper’s eyes, crafted from alabaster, crystal, and black stone, are rimmed with copper to mimic eyeliner, bringing an uncanny vitality to his gaze. These lifelike eyes not only animate the priest’s face but also seem to reflect his self-important personality.

The Art of Ancient Realism

A Portrait of Prosperity

Kaaper stands proudly, his posture more akin to traditional bas-relief figures than stone statues. He is depicted mid-stride, holding a staff of power (now replaced with a copy) and likely a cylinder, dressed in a long kilt tied below his navel. The statue originally bore a light coat of painted plaster, traces of which still remain, portraying with striking realism the satisfied opulence of a man content with his social standing.

Craftsmanship Beyond Stone

Unlike their stone counterparts, wooden sculptures like Kaaper’s offered ancient artists greater freedom. The arms were modeled separately and attached to the body, a common technique in wooden statuary that allowed for more dynamic poses. This approach freed the figure from the constraints of stone carving, resulting in a more lifelike representation.

A Legacy Carved in Wood

Today, the Statue of Kaaper, still affectionately known as Sheikh el-Balad, stands as a testament to the skill of ancient Egyptian craftsmen. Its remarkably naturalistic features continue to captivate visitors at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, offering a window into the life of a high-ranking priest from over 4,000 years ago. This wooden wonder not only survived the millennia but also carries with it a nickname born from the awe it inspired in its modern discoverers – a true bridge between ancient craftsmanship and enduring human connection.