Cambridge University Unravels a Bizarre Pattern

A groundbreaking study from the University of Cambridge has revealed a peculiar evolutionary pattern for the Homo lineage, challenging conventional wisdom about the rise and fall of early human ancestors. The research, published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, suggests that interspecies competition played a pivotal role in shaping our evolutionary trajectory, producing a “bizarre” twist unlike almost anything else in the natural world.

Competition: The Driving Force

Traditionally, climate has been considered the primary factor influencing the emergence and extinction of hominin species. However, this new study highlights the importance of competition between species, a well-established concept in vertebrate evolution but often overlooked in the context of human ancestors.

Lead author Dr. Laura van Holstein, a biological anthropologist from Clare College, University of Cambridge, explains:

“We have been ignoring the way competition between species has shaped our own evolutionary tree. The effect of climate on hominin species is only part of the story.”

The Typical Pattern

For most vertebrates, species formation occurs when ecological “niches” become available, allowing new species to emerge and fill those vacant roles. This pattern is evident across various groups, including Darwin’s famous finches, where different beak shapes evolved to exploit specific food sources.

Van Holstein’s research, employing Bayesian modeling and phylogenetic analyses, reveals that early hominins followed a similar trend. Speciation rates increased until competition for resources or space became intense, at which point extinction rates rose, mirroring the patterns observed in other mammals.

The Bizarre Twist

However, when the researchers analyzed the Homo lineage – the branch that ultimately led to modern humans – they encountered a striking anomaly. Contrary to the typical pattern, interspecies competition within the Homo group appeared to drive the emergence of even more new species, a complete reversal of the trend seen in almost all other vertebrates.

Van Holstein elaborates:

“The more species of Homo there were, the higher the rate of speciation. So when those niches got filled, something drove even more species to emerge. This is almost unparalleled in evolutionary science.”

The closest parallel the researchers could find was in the evolution of beetle species on islands, where contained ecosystems can produce unusual evolutionary trends.

Filling the Gaps

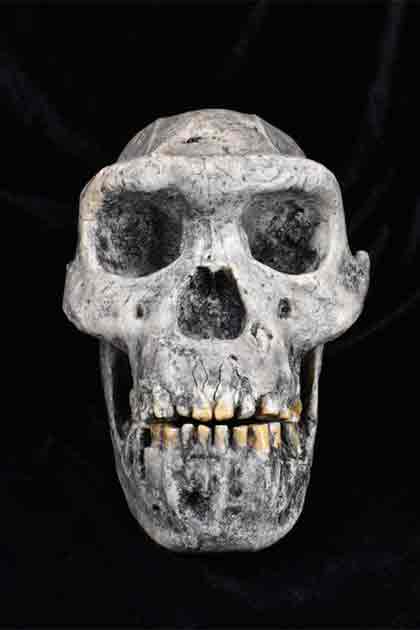

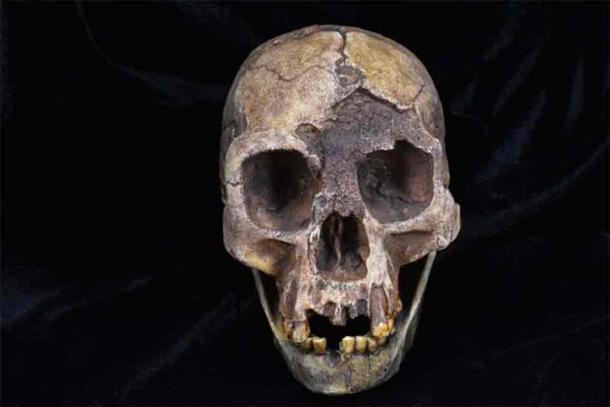

To conduct this groundbreaking study, van Holstein created a comprehensive database of hominin fossil occurrences, encompassing around 385 instances where examples of a species were found and dated.

Acknowledging the limitations of the fossil record, van Holstein cautions:

“The earliest fossil we find will not be the earliest members of a species. How well an organism fossilizes depends on geology and climatic conditions, and with research efforts concentrated in certain parts of the world, we might well have missed younger or older fossils of a species as a result.”

This study not only revises the start and end dates for many early human ancestors but also challenges our understanding of the forces that shaped our evolutionary journey, revealing a unique and “bizarre” twist in the path that ultimately led to modern humans.