A Renaissance-Era Tragedy Uncovered

A “virtual autopsy” conducted on the mummified remains of a toddler buried inside a family crypt in Austria has revealed a heartbreaking tale of malnutrition and early demise. The study, published in the journal Frontiers in Medicine, sheds light on the unfortunate fate of a young boy believed to be Reichard Wilhelm, the first-born son of a Count of Starhemberg – a prominent member of the Austrian aristocracy during the Renaissance era.

A Privileged Life, a Somber End

Despite his privileged upbringing, the team of German scientists concluded that the young boy, who lived between the 14th and 17th centuries and died when he was just 10 to 18 months old, experienced “extreme nutritional deficiency and a tragically early death from pneumonia.”

The Telltale Signs of Vitamin D Deficiency

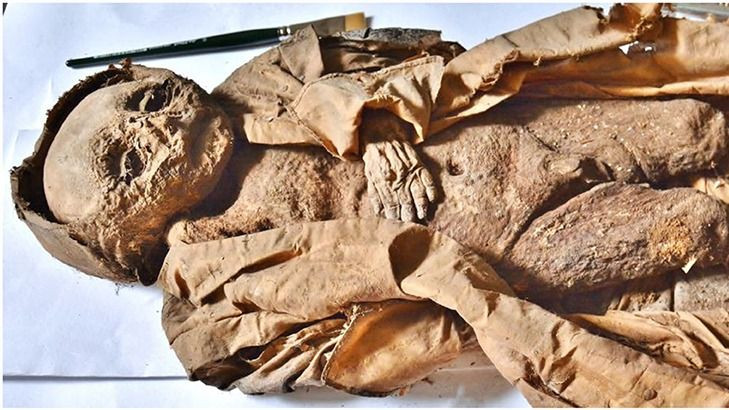

The CT scans performed on the mummy, found wrapped in a hooded silk coat with his left hand draped across his abdomen, revealed malformations on his ribs – classic signs of malnutrition, indicative of a condition known as rickets. These malformations, termed a “rachitic rosary,” occur when knobs of rib bone begin to resemble rosary beads due to a severe vitamin D deficiency.

A Paradoxical Condition

Interestingly, the boy’s remaining soft tissues showed that he was overweight at the time of his death, eliminating the possibility of underfed. According to Andreas Nerlich, the study’s lead author and a pathologist from the Academic Clinic Munich-Bogenhausen in Germany, “The combination of obesity along with a severe vitamin deficiency can only be explained by a generally ‘good’ nutritional status along with an almost complete lack of sunlight exposure.”

A Resting Place Fit for Nobility

The child was found buried inside a wooden coffin that proved too small for him, as evidenced by the deformation of his skull. The crypt where he was laid to rest was reserved exclusively for descendants of the Counts of Starhemberg, specifically their first-born sons who would have been titleholders, as well as the men’s wives.

Radiocarbon dating of a skin sample suggested he was buried between 1550 and 1635, although building records indicate that the crypt underwent a renovation around 1600, suggesting he was likely buried after that date. He was the youngest person buried in the crypt.

Nerlich emphasizes the need to “reconsider the living conditions of high aristocratic infants of previous populations,” as this tragic case highlights the unexpected perils that even the privileged could face in the absence of proper sunlight exposure.