A Shocking Discovery

In 1971, a remarkable find was made near Changsha, China. Workers excavating an area near an air raid shelter stumbled upon a massive tomb belonging to Xin Zhui, also known as Lady Dai. Inside, they uncovered a trove of over 1,000 precious artifacts, including makeup, lacquerware, and intricately carved wooden figures depicting her retinue of servants.

What astonished researchers even more than the tomb’s opulence was the astonishing state of preservation of Xin Zhui’s physical remains. Not only were her belongings well-preserved, but her own body exhibited remarkable signs of preservation, offering a rare glimpse into the past and captivating the imaginations of scholars and archaeologists alike.

Baffling Discoveries

An Autopsy Unlike Any Other

Scientists conducted an autopsy on Xin Zhui’s body and made astounding discoveries. Her skin retained its softness, moisture, and elasticity, resembling that of a living person. Her original hair, including eyebrows and lashes, was still intact. Despite her age, her organs remained undamaged, and her veins contained type-A blood.

The presence of blood clots revealed that Xin Zhui’s cause of death was a heart attack. Additionally, researchers found various health conditions such as gallstones, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and liver disease.

The Secret to Eternal Preservation

Meticulous Burial Techniques

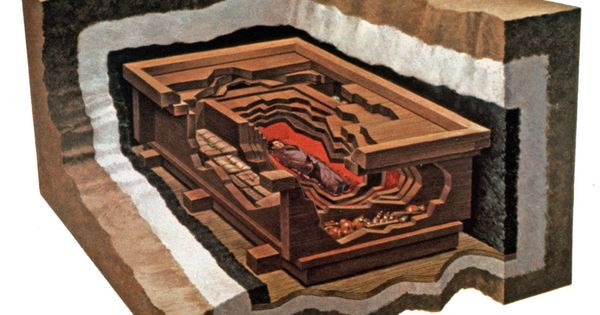

The preservation of Lady Dai’s mummy can be attributed to the airtight and elaborate tomb in which she was buried. Placed in four nested pine coffins, Xin Zhui was enveloped in multiple layers of silk fabric and submerged in a slightly acidic liquid. The tomb was lined with moisture-absorbing charcoal and sealed with clay to prevent decay-causing bacteria and oxygen from entering. The meticulous sealing techniques and protective measures contributed to the exceptional preservation of Xin Zhui’s remains.

A Glimpse into the Past

The Life of Xin Zhui

While Xin Zhui’s burial and cause of death are well-documented, information about her life remains somewhat limited. She held the esteemed position of being the wife of Li Cang, the Marquis of Dai, who served as a prominent Han official during that time. Tragically, Xin Zhui met her untimely demise at the age of 50 due to a heart attack, which was likely a result of a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and a diet characterized by extravagant indulgence.

Today, Xin Zhui’s mummified body finds its resting place in the Hunan Provincial Museum, where it continues to captivate both researchers and the public alike. Her exceptionally preserved remains have become a focal point for ongoing studies in the field of corpse preservation. Through the examination of her body and the artifacts surrounding her, experts gain invaluable insights into the lifestyle, health, and cultural practices of ancient China’s elite during the Han dynasty. Xin Zhui’s legacy as the astonishingly intact Lady Dai mummy lives on as a testament to the extraordinary preservation techniques of the past and the endless wonders they unveil to us in the present day.