Uncovering an Ancient Marvel

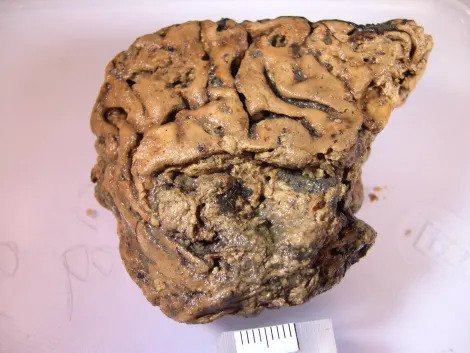

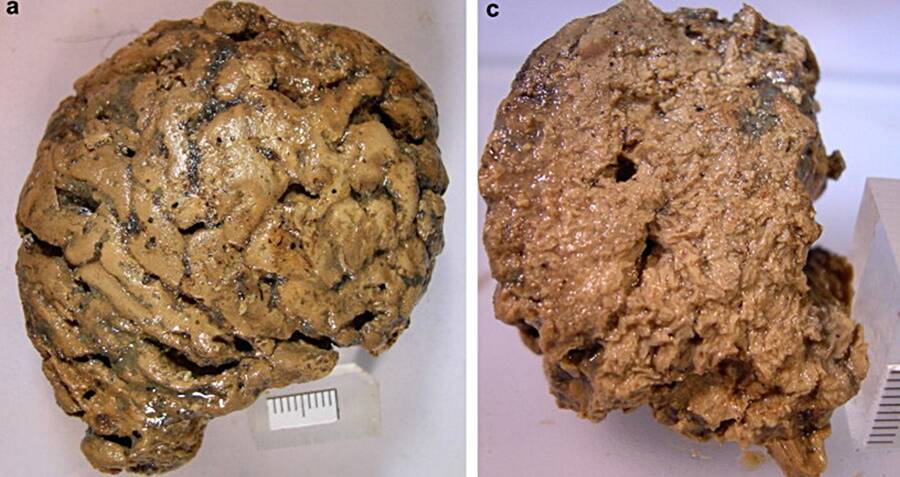

In 2008, a remarkable discovery was made in a mud pit in Heslington, Yorkshire, England – a 2,600-year-old human brain, remarkably well-preserved and hailed as the oldest and best-preserved brain ever found in Eurasia. Dating back to the Iron Age between 482 and 673 BC, this extraordinary find, dubbed the “Heslington brain,” has captivated scientists worldwide and offered an unprecedented opportunity to study the intricacies of the human brain at a molecular level.

The Enigma of Preservation

For over two millennia, this ancient brain defied the natural processes of decomposition, prompting researchers to unravel the mysteries behind its remarkable preservation. Through meticulous analysis and cutting-edge microscopy techniques, an international team of experts embarked on an unprecedented journey to explore the brain tissue at a molecular level.

Unraveling the Secrets of Protein Aggregation

The team’s groundbreaking research, published in the Royal Society Interface Journal, revealed the presence of more than 800 proteins within the tissue sample. Some of these proteins were found to be in remarkably good condition, offering invaluable insights into their intricate structures and functions.

Remarkably, the scientists discovered that these proteins had folded themselves into tight-packed, stable aggregates – a configuration far more stable than those found in normal, healthy brains today. This unique aggregation process is believed to have played a crucial role in the brain’s preservation, effectively shielding it from the ravages of time and decomposition.

Implications for Brain Disease Research

The discovery of these tightly packed protein aggregates has profound implications for our understanding of brain diseases, particularly those associated with protein misfolding and aggregation, such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Shedding Light on Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease

Diseases like dementia and Alzheimer’s involve the formation of rogue proteins, known as amyloid and tau, which clump together and contribute to the death of brain cells. Intriguingly, the process of aggregate formation observed in the Heslington brain appears to have played a protective role, enabling the preservation of brain proteins for over two millennia.

This remarkable finding provides new evidence for the long-lasting stability of non-amyloid protein aggregates, offering a unique opportunity for scientists to study the mechanisms that govern protein preservation in the human brain.

A Beacon of Hope in Brain Disease Research

As dementia and Alzheimer’s disease continue to affect millions of people worldwide, the Heslington brain offers a glimmer of hope for future research. By leveraging the insights gained from studying this ancient marvel, scientists may uncover new strategies to combat these devastating conditions and potentially develop groundbreaking therapies or preventative measures.

With its extraordinary preservation and the wealth of molecular information it holds, the Heslington brain stands as a testament to the resilience of the human body and a beacon of hope for those affected by brain disorders. As research continues, this remarkable find may unlock the secrets to preserving and protecting the intricate workings of the human brain, paving the way for a future where brain diseases are better understood and treated more effectively.