The Discovery of Skull Masks in Tenochtitlán

Over thirty years ago, archaeologists unearthed eight alarming masks crafted from human skulls at a temple in Tenochtitlán, Mexico. Their origins and intended use have long bewildered experts. Recent archaeological insights indicate that these eerie masks may have been fashioned from the remains of slain warriors and distinguished members of the ancient Aztec elite.

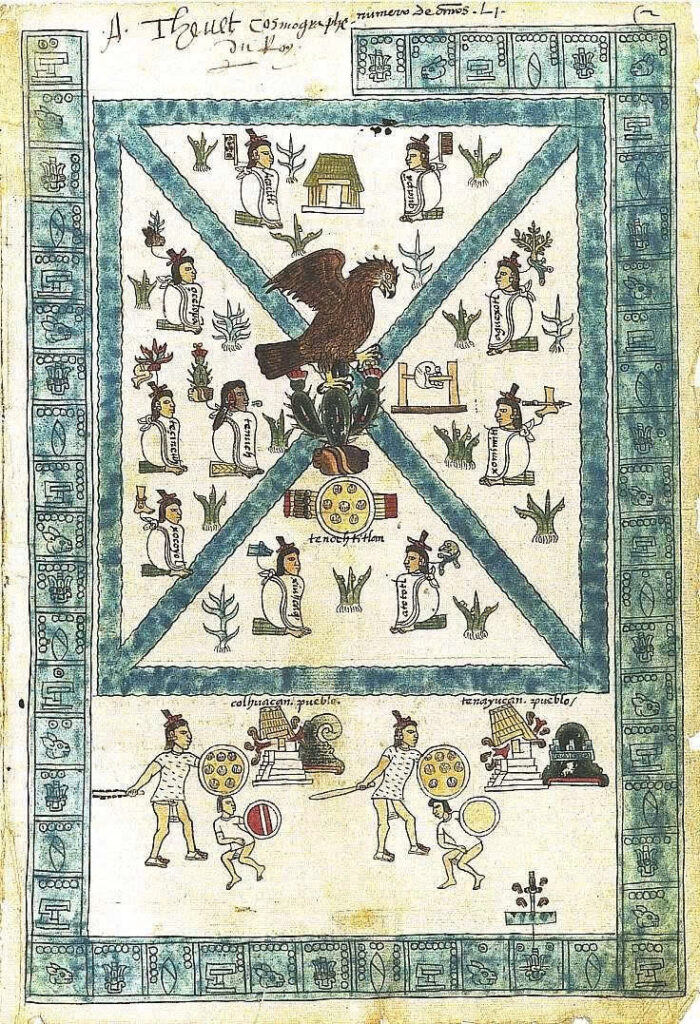

The Significance of Templo Mayor

The Templo Mayor, revered as the religious and political nucleus of Tenochtitlán, served as the heart of the Aztec Empire in the 15th century AD. Dedicated to Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and the sun, this temple is a focal point of evidence revealing the prevalence of human ritual sacrifice—an integral aspect of Aztec spirituality. Practices included beheading, heart extraction, and ceremonial combat, making the discovery of the skull masks particularly striking even within the context of ritual sacrifice.

Insights from Archaeological Analysis

A team of anthropologists, led by Corey Ragsdale from the University of Montana, endeavored to analyze the skull masks and other ritual skull offerings to uncover their origins and creation methods. Their findings were published in the June edition of Current Anthropology.

The masks were described as decorative headpieces made from human skulls, designed to be worn over the face or integrated into headdresses. Modifications included the removal of the back cranium, the application of dyes, and the insertion of decorative elements in the eye sockets and nasal cavities.

Who Became a Skull Mask?

To determine the identities of those transformed into masks, Ragsdale and his team examined both modified and unmodified skulls for indicators of age, sex, and health conditions. They discovered that all skull masks originated from males aged 30 to 45, remarkably free from dental diseases and nutritional stress, suggesting that these individuals were healthier than typical for their society.

Upon analyzing the dental structures and comparing them with known groups, the researchers concluded that these men hailed from diverse regions, including the Toluca Valley and various Aztec towns. This non-invasive analysis was corroborated by isotopic studies, affirming the effectiveness of their methods in tracing the origins of these individuals.

Video

The Craftsmanship of Skull Masks

The researchers also delved into the manufacturing techniques of the skull masks. By replicating the cut marks and drill holes observed on the skulls using period-appropriate stone tools, they revealed that these modifications closely resembled those found in other artifacts from Templo Mayor. This led them to propose that the individuals whose skulls were made into masks were likely brought to Tenochtitlán specifically for sacrifice.

Drawing from the comprehensive data, the team concluded that the skull masks were likely crafted from the remains of captured warriors or executed nobility, possibly including the defeated king of Tollocan, as historical records suggest.

The Broader Context of Human Sacrifice sacrifice was a prevalent practice in the Aztec Empire, with historical accounts suggesting that at least 20,000 individuals met this fate at Tenochtitlán alone. Most victims were war captives or tribute offerings, often ending up in mass graves. However, Ragsdale’s study reveals that the Aztec approach to sacrifice varied significantly; the creation of skull masks appears to be a distinguished privilege reserved for elite warriors and nobility.

Future Research Directions

Ragsdale plans to extend his research to several tzompantlis—skull racks used for displaying sacrificial victims—from Templo Mayor and beyond. His forthcoming analyses will incorporate 3D scanning of facial skeletons to gain deeper insights into the appearances of these individuals, further illuminating the rituals and customs of the ancient Aztec civilization.