In the dusty plains of northern Iraq, where the mighty Assyrian Empire once stretched its dominion, lies one of archaeology’s most fascinating stories. The tale of Sargon II’s magnificent palace at Khorsabad speaks of imperial dreams, divine protection, and the relentless passage of time that buried an entire civilization until French explorers brought it back to light.

The Rise of a Royal Vision

During the 8th century BCE, when the Neo-Assyrian Empire dominated the ancient Near East, King Sargon II ruled with unprecedented power from approximately 722 to 705 BCE. Around 713 BCE, this ambitious monarch conceived a bold plan to demonstrate his supreme authority: the construction of an entirely new capital city.

Building the “Fortress of Sargon”

At the base of Mount Musri in what is now northern Iraq, Sargon II established Dûr-Sharrukin—literally meaning “Sargon’s Fortress.” This wasn’t merely another city; it was intended to be the largest urban center the ancient world had ever witnessed. Utilizing the wealth from military conquests and the labor of prisoners of war, the king embarked on creating a symbol of his divine power.

The centerpiece of this magnificent undertaking was a sprawling royal palace containing approximately 200 chambers and courtyards. The scale of construction was breathtaking, representing not just architectural ambition but also the vast reach of the Assyrian Empire, which extended across enormous territories from Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean.

The Curse of an Unfinished Dream

A King’s Mysterious End

Tragedy struck in 705 BCE when Sargon II perished in a fierce battle, his body never recovered from the battlefield. This mysterious disappearance sent shockwaves through the empire, as the absence of a proper royal burial was interpreted as a sign of divine displeasure. The king’s son and heir, Sennacherib, faced with these ominous portents, made a fateful decision.

Abandonment and Oblivion

Rather than complete his father’s grandiose project, Sennacherib chose to establish his own capital at Nineveh, where he had previously served as regent. The magnificent but incomplete city of Khorsabad was abandoned, its grand palaces and courtyards left to the mercy of time and sand. For over a millennium, the site lay forgotten, known only through ancient texts and biblical references.

The French Discovery That Changed History

Archaeological Breakthrough

The sleeping city remained hidden until 1843, when Paul Émile Botta, serving as French vice-consul in Mosul, began the excavations that would revolutionize our understanding of the ancient world. Botta’s pioneering work marked the birth of Mesopotamian archaeology and Near Eastern studies as scientific disciplines.

The World’s First Assyrian Museum

The treasures unearthed at Khorsabad were so remarkable that they led to the establishment of the world’s first Assyrian museum at the Louvre in Paris. On May 1, 1847, this groundbreaking exhibition opened its doors, introducing the public to a lost civilization that had previously existed only in ancient texts and religious scriptures.

Artistic Splendor Frozen in Stone

Royal Decorations and Their Faded Glory

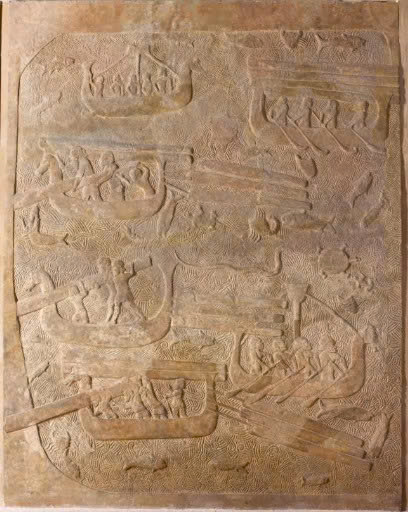

The palace walls were adorned with massive carved alabaster panels that once gleamed with vibrant colors—brilliant blues and reds that have largely faded over the millennia. These monumental stone slabs, many weighing several tons, originally decorated the open courtyards leading to the throne room.

The intricate low-relief carvings tell vivid stories of court life and royal power. Scenes of archers engaged in hunts, processions of dignitaries, and the transportation of precious cedar wood from Lebanon all serve to glorify Sargon II’s reign while documenting the impressive scope and speed of his building projects.

The Eternal Guardians

Perhaps most impressive among the palace decorations were the protective spirits known as lamassu or aladlammû. These magnificent creatures, each carved from a single massive alabaster block weighing approximately 28 tons, stood guard at crucial entrances and passageways.

Video

The Magic of Mesopotamian Protection

Divine Hybrid Beings

The lamassu represent a masterful fusion of symbolic elements: the powerful body and keen ears of a bull, the soaring wings of an eagle, and the crowned head of a human bearing striking resemblance to Sargon II himself. Their multiple sets of horns—two or three pairs—marked them as divine beings in Mesopotamian belief systems.

Benevolent Guardians

Unlike many ancient protective deities, these monumental guardians were conceived as benevolent forces. Their gentle expressions, complete with subtle smiles, conveyed their role as protectors rather than intimidators. They combined the strength of the bull, the vision of the eagle, and the wisdom of humanity to create the ultimate safeguards for the palace and its inhabitants.

Legacy of a Lost Empire

Today, visitors to museums around the world can witness the magnificence of Sargon II’s vision through the artifacts recovered from Khorsabad. These ancient treasures continue to tell the story of an empire that stretched across continents, a king whose ambitions knew no bounds, and the skilled craftsmen who created art that has survived nearly three millennia.

The tale of Khorsabad remains one of archaeology’s greatest success stories—a reminder that beneath the sands of time lie civilizations waiting to share their stories with the modern world. Through the dedication of early archaeologists like Paul Émile Botta, we can still walk among the stone guardians that once protected the dreams of an ancient king, their gentle smiles welcoming visitors to a world that was lost but never truly forgotten.