An Immersive Experience

In March 2022, I had the privilege of visiting the National Museum of Ireland on Kildare Street, Dublin. This remarkable archaeology museum, offering free admission to the public, is a must-visit destination for anyone in the city. The thoughtful and respectful display of human remains, securely presented behind glass and carefully illuminated, left a profound impression on me.

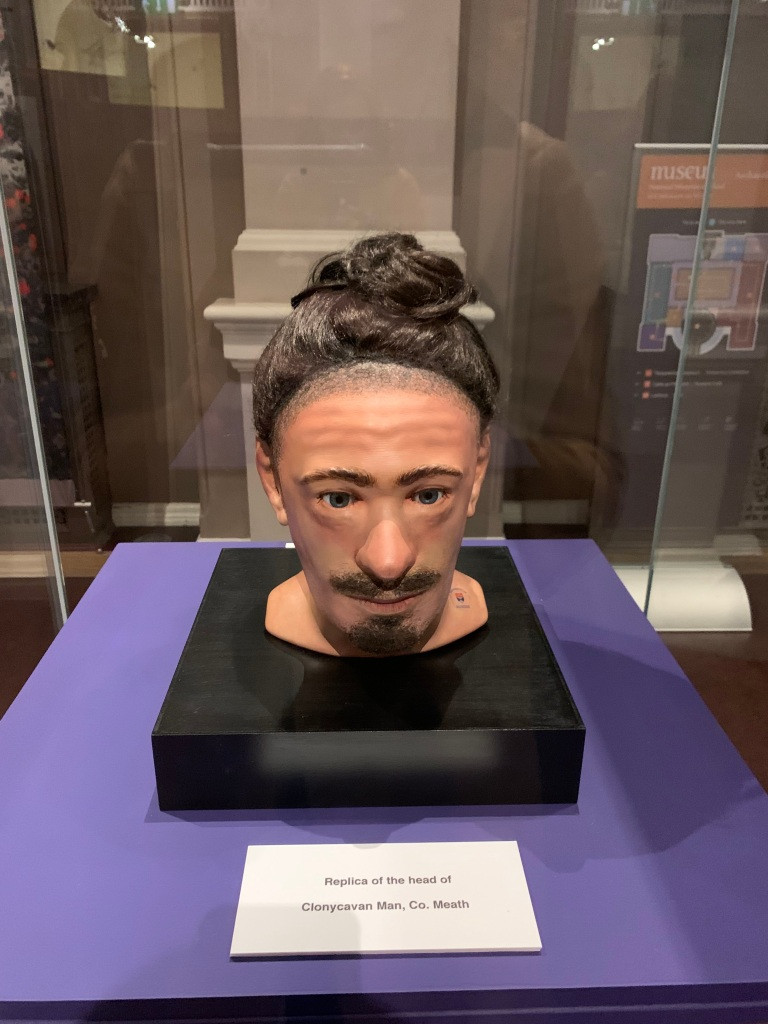

Clonycavan Man: A Face from the Past

Connecting with a Tragic Story

One of the most striking exhibits was the Clonycavan Man, part of the Kinship and Sacrifice section showcasing Irish bog bodies. Discovered in 2003, Clonycavan Man is believed to have been a murder victim, bearing signs of ritualistic mutilation. His reconstructed face allowed visitors to connect with him on a personal level, despite the change in color due to the bog’s anaerobic conditions.

The Viking Warrior’s Resting Place

Remnants of a Bygone Era

Another noteworthy display was an almost fully intact skeleton dating back to the 9th century, found at Memorial Park, Island Bridge, Dublin. Labeled as belonging to a warrior, the remains were accompanied by a dagger and sword, leaving visitors to ponder the individual’s gender and the significance of the dimly lit exhibit.

Burial 24: A Subtle Presence

Recognizing the Unseen

Burial 24, located in the Hill of Tara section, contained the remains of a cremated adult, accompanied by an inverted encrusted urn and vase. Visitors might have easily overlooked the human remains if not for the exhibit’s label, prompting questions about how we perceive and recognize such displays.

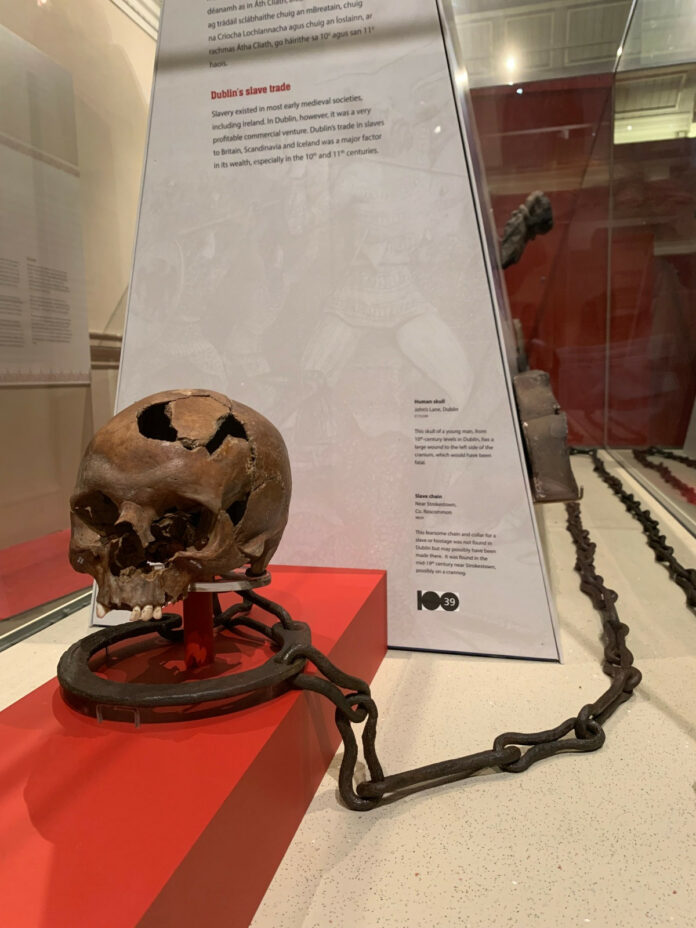

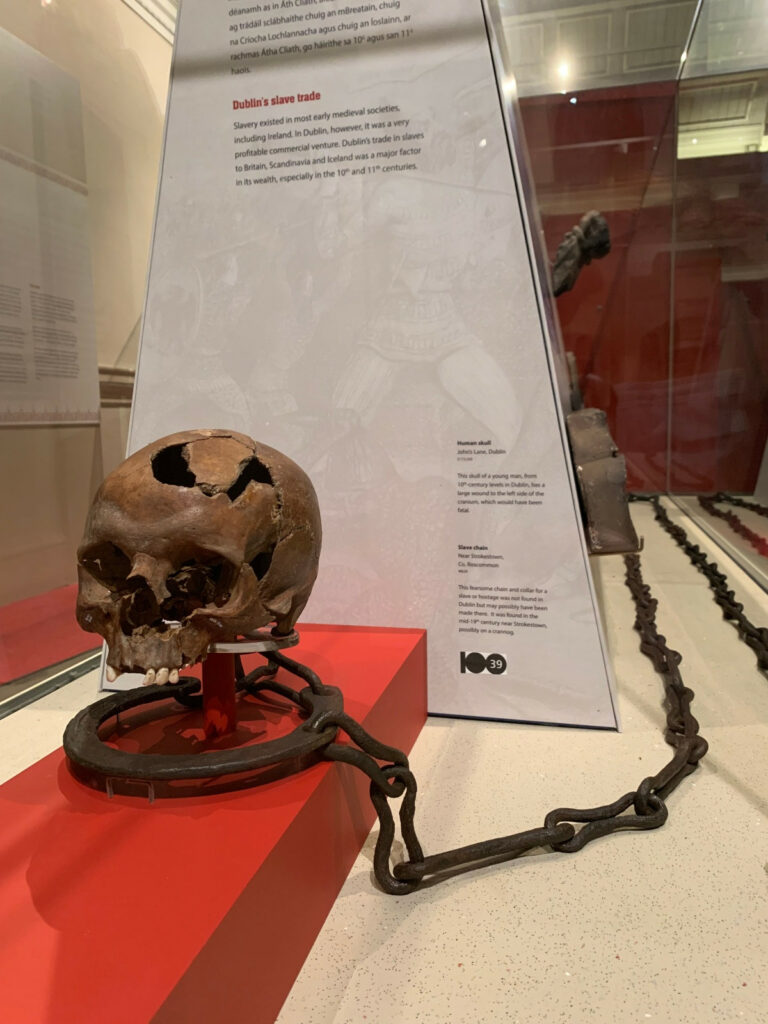

The Skull from John’s Lane

Provoking Uncomfortable Reflections

A thought-provoking exhibit centered around a human skull discovered at John’s Lane, Dublin. The inclusion of a “slave chain” alongside the skull, which belonged to a young man who may have suffered a fatal head wound, evoked discomfort and raised questions about identity and the post-mortem integrity of the individual.

The Ptolemaic Mummy

Echoes of Ancient Egypt

The museum’s upper galleries housed a significant collection of objects from ancient Egypt, including several mummies acquired from excavations conducted between the 1890s and 1920s. One notable exhibit was the Ptolemaic Mummy of unknown provenance, dating back to around 300 BC. Unlike other museums, there was no explicit warning about the display of human remains, but the wrapped mummies created a layer between the viewer and the preserved bodies.

A Thought-Provoking Journey

The National Museum of Ireland’s Archaeology section offers a captivating and thought-provoking experience through its display of human remains. These exhibits serve not only as educational resources but also as catalysts for discussions on death, identity, and the representation of the human body, challenging visitors to reflect on the ethics and boundaries of displaying human remains.