In the shadowy depths of Central and South American jungles, magnificent civilizations once flourished, only to be reclaimed by nature after their decline. For centuries, these architectural wonders remained hidden, known only through whispered legends and local folklore. It wasn’t until the 19th century that a remarkable generation of explorers ventured into these forbidding landscapes, armed with nothing but rudimentary maps, basic tools, and an insatiable curiosity about the past.

The Forgotten Empires: Maya and Inca Civilizations

The dense, unforgiving jungles of Mesoamerica and the towering Andean mountains concealed breathtaking achievements of human ingenuity. Cities with advanced water systems, astronomical observatories, and monumental architecture lay forgotten under centuries of vegetation and earth. While local indigenous communities maintained connections to these ancestral places through oral traditions, the wider world remained largely unaware of their existence.

As rumors of these “lost cities” reached European and North American ears, they ignited the imagination of adventurers seeking fame, fortune, and scientific recognition. What they ultimately discovered would challenge Western assumptions about the capabilities of ancient peoples and forever change our understanding of pre-Columbian history.

The Visionary Partnership: Stephens and Catherwood

A Diplomat and an Artist Unite

The story of rediscovery begins with an unlikely partnership formed in 1839. John Lloyd Stephens, an American diplomat appointed as U.S. Ambassador to Central America, joined forces with Frederick Catherwood, a British artist renowned for his architectural drawings. Together, they embarked on expeditions that would transform our understanding of ancient Mesoamerican civilizations.

Stephens brought diplomatic credentials that facilitated their travels, while Catherwood contributed his extraordinary artistic talent. Their collaboration proved revolutionary as they documented Maya sites across Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico with unprecedented detail and accuracy.

Unveiling Maya Magnificence

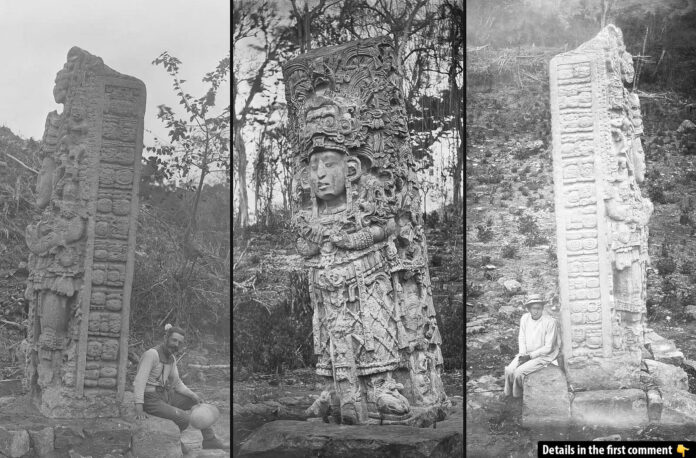

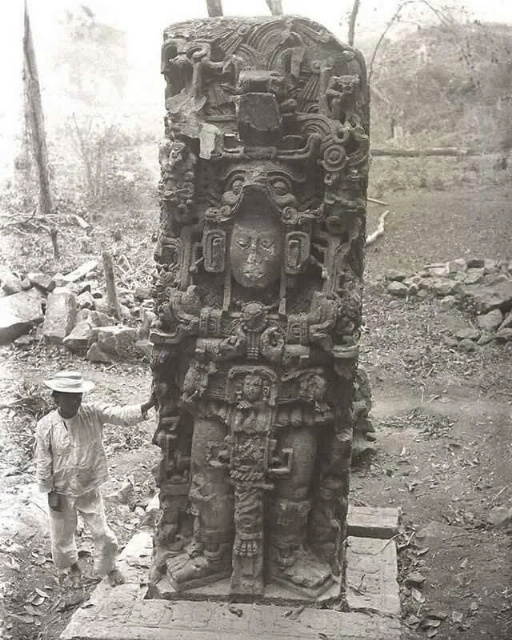

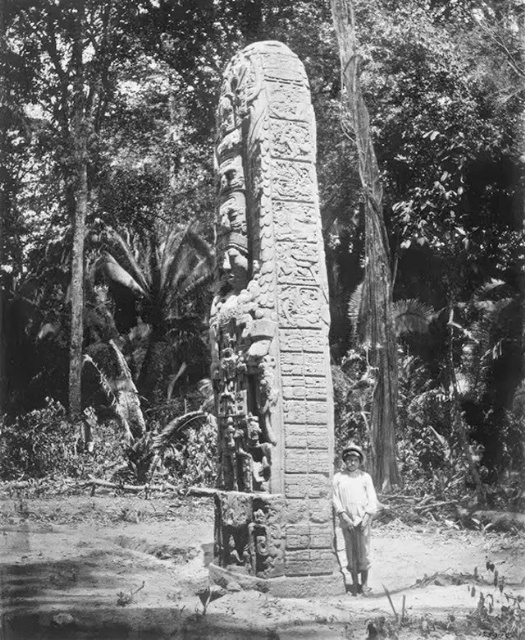

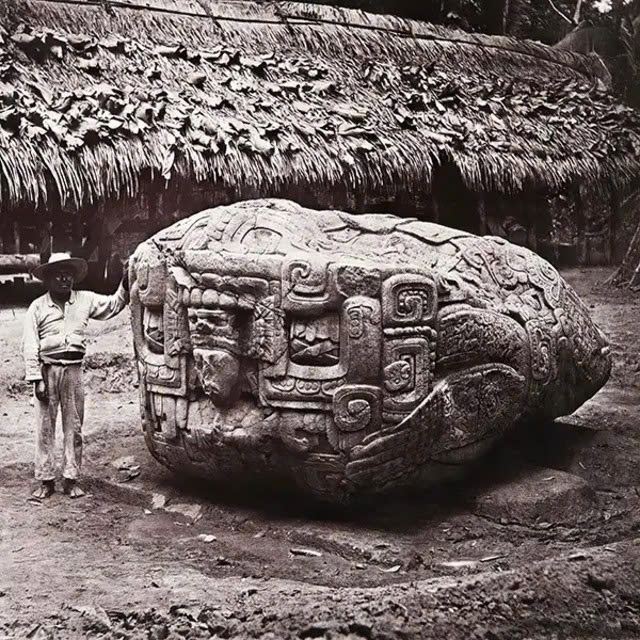

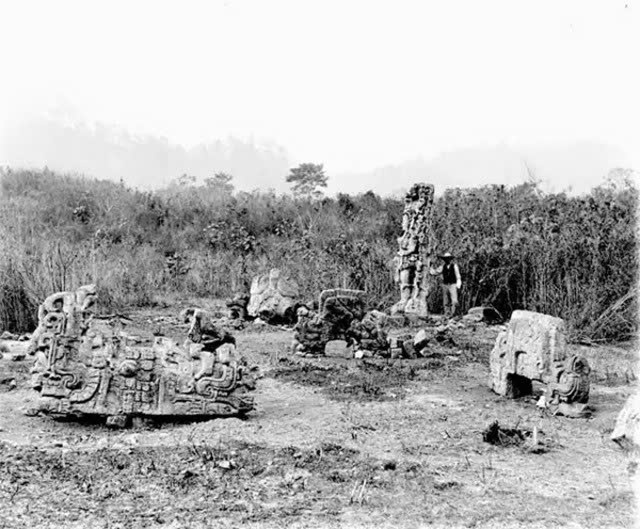

At Copán in Honduras, Stephens was mesmerized by the intricate stone carvings adorning the site’s stelae and altars. In his writings, he emphatically rejected the prevailing notion that these monuments were created by Old World civilizations, insisting instead that they were the work of indigenous peoples. Catherwood’s exquisite illustrations captured the grandeur of these monuments with remarkable precision, despite the challenging conditions of working in the jungle.

Their published accounts, particularly “Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatán,” became an immediate sensation across Europe and America. The detailed drawings and vivid descriptions brought the lost Maya world to life for readers and inspired subsequent generations of explorers and archaeologists.

The Scientific Pioneer: Alfred Percival Maudslay

Bringing Photography to the Jungle

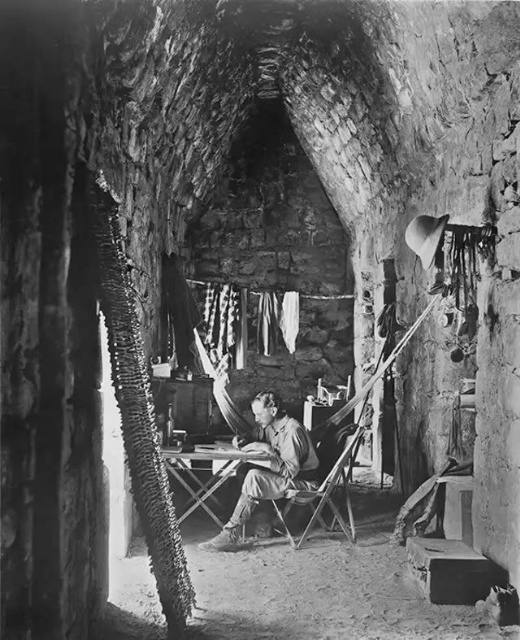

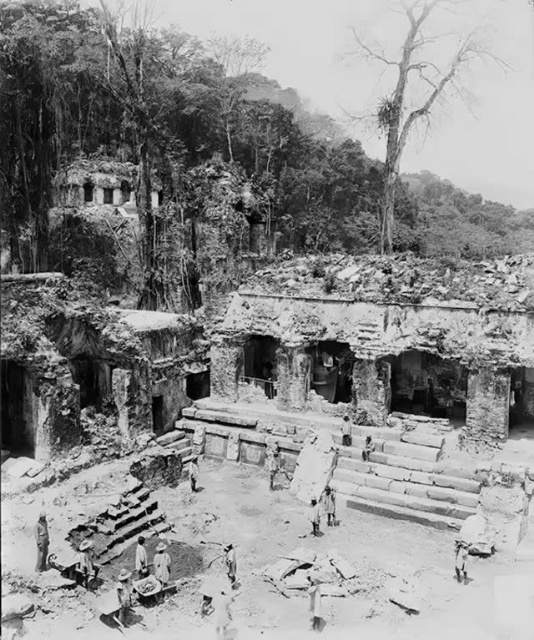

As the 19th century progressed, explorers began employing new technologies in their quest to document ancient civilizations. Alfred Percival Maudslay, a British archaeologist, revolutionized archaeological documentation by bringing the emerging technology of dry plate photography to Maya sites in the 1880s.

Maudslay’s methodical approach set new standards for archaeological fieldwork. At Copán, Quiriguá, and Chichén Itzá, he created the first comprehensive photographic record of Maya monuments, hieroglyphs, and architectural features. These images provide a remarkable window into the state of these sites before modern conservation efforts and tourism.

Preservation Through Innovation

Recognizing that many monuments faced deterioration from exposure to the elements, Maudslay employed innovative techniques to preserve their details for future study. He hired Italian craftsmen to create plaster and papier-mâché casts of important carvings and inscriptions, essentially creating a portable museum of Maya art and writing.

These casts, many of which ended up in museums, proved crucial for scholars working to decipher Maya hieroglyphs in the 20th century. Maudslay’s painstaking documentation of architectural features and spatial relationships also provided vital contextual information that earlier explorers had often overlooked.

The Controversial “Discoverer”: Hiram Bingham and Machu Picchu

The Quest for the Lost City of the Incas

In 1911, an American historian named Hiram Bingham ventured into the rugged Andes Mountains of Peru. Driven by ambition and fascination with Inca history, Bingham sought to locate Vilcabamba, the legendary last refuge of the Inca rulers who had resisted Spanish conquest.

On July 24, guided by a local farmer named Melchor Arteaga, Bingham ascended a steep mountain ridge to find an astonishing sight: the nearly intact remains of an Inca citadel perched among the clouds. This was Machu Picchu, a site that would soon become one of the most recognizable archaeological treasures in the world.

Recognition and Controversy

Bingham’s subsequent excavations revealed the architectural brilliance of the Incas. The precision stonework, elaborate terracing systems, and astronomical alignments demonstrated sophisticated engineering knowledge that had allowed the Incas to build a sustainable city in a seemingly impossible location.

However, Bingham’s role has become increasingly controversial. While he brought international attention to Machu Picchu through his National Geographic articles and books, he was certainly not the first outsider to visit the site. Local residents had known of its existence for generations, and other visitors, including Agustín Lizárraga, had preceded Bingham. Moreover, Bingham’s removal of artifacts to Yale University sparked an ownership dispute that wasn’t resolved until 2012, when the items were finally returned to Peru.

The Unsung Heroes: Indigenous Knowledge and Local Guides

Behind every “discovery” stood indigenous guides whose knowledge proved indispensable. Men like Gorgonio López, who guided Maudslay through the jungles of Central America, possessed intimate knowledge of the terrain and local traditions that often pointed explorers toward important sites.

Similarly, Melchor Arteaga’s familiarity with the mountains around Machu Picchu was crucial to Bingham’s expedition. Without these local collaborators, many sites might have remained hidden from outside eyes for decades longer.

Unfortunately, the contributions of these indigenous guides have often been minimized in historical accounts that celebrate the achievements of European and American explorers. The rediscovery narrative sometimes obscures the fact that these places were never truly “lost” to local communities who maintained cultural and sometimes physical connections to them.

Monuments in Stone and Ink: The Documentation Legacy

Artistic Impressions

Frederick Catherwood’s illustrations remain among the most evocative records of Maya sites as they appeared in the 19th century. Working in challenging conditions, often with rain threatening to ruin his papers and insects disrupting his concentration, Catherwood created meticulously detailed drawings that captured the grandeur and artistic sophistication of Maya monuments.

His illustrations helped readers visualize structures that would have otherwise seemed fantastical in written descriptions alone. The artistic quality of his work also elevated Maya art in the estimation of Western audiences, presenting it as worthy of serious aesthetic consideration rather than mere curiosity.

Photographic Records

Maudslay’s photographs provided an unprecedented level of accuracy in archaeological documentation. Unlike drawings, which inevitably reflected the artist’s interpretation, photographs offered a more objective record of sites as they existed at a specific moment in time.

These visual records have proven invaluable for conservation efforts, allowing archaeologists to track the deterioration of monuments over time and to guide restoration work. They also preserve images of carvings and inscriptions that have since been damaged by weathering, looting, or earlier misguided conservation attempts.

Video

The Explorers’ Legacy: Foundations of Modern Archaeology

The expeditions of these early adventurers transformed our understanding of pre-Columbian civilizations and laid the groundwork for modern archaeological practices. Their documentation efforts, particularly Maudslay’s systematic approach, established standards for recording sites that influenced subsequent generations of researchers.

The collections they assembled—including artifacts, casts, drawings, and photographs—have provided valuable resources for scholars working to understand the history, art, and culture of ancient American civilizations. Their published accounts also generated public interest in archaeology and helped secure funding for future expeditions and preservation efforts.

However, their legacy is complicated by ethical questions about the removal of artifacts and the representation of indigenous histories. Many objects collected during these expeditions ended up in European and North American museums, raising questions about cultural heritage and ownership that continue to resonate today.

Conclusion: Rediscovery and Recognition

The rediscovery of Maya and Inca civilizations stands as a testament to human curiosity and perseverance. Through the efforts of explorers like Stephens, Catherwood, Maudslay, and Bingham—and the often overlooked contributions of their indigenous guides—the world gained a deeper appreciation for the artistic, architectural, and cultural achievements of ancient American peoples.

Today, sites like Copán, Chichén Itzá, and Machu Picchu attract millions of visitors annually, testifying to the enduring fascination with these remarkable civilizations. As we continue to study and preserve these places, we honor not only the ancient builders who created them but also the explorers who brought them to global attention and the indigenous communities who never forgot them.

The jungle explorers of the 19th century may have navigated through physical vegetation, but they also helped clear away the overgrowth of cultural misunderstanding and prejudice that had obscured the true achievements of America’s ancient civilizations. Their legacy reminds us that the past is never truly lost—it simply waits to be rediscovered by those willing to seek it out.