In the depths of Brazil’s Amazon rainforest, where sunlight filters through dense canopies and rivers wind like ancient serpents, approximately 100 tribes remain untouched by modern civilization. These aren’t remnants of a forgotten past, but vibrant communities who have deliberately chosen isolation—a decision born from historical trauma and a profound connection to their ancestral lands.

The Forest Guardians

A Choice of Isolation

The story of Brazil’s uncontacted tribes begins with violence. During the rubber boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, countless Indigenous communities faced enslavement, displacement, and genocide. Those who survived fled deeper into the forest, carrying with them memories that continue to shape their isolation today.

“These communities aren’t primitive or ‘undiscovered’,” explains Paulo Meirelles, a former FUNAI official who spoke at a recent conservation conference. “They are making an active choice to avoid contact based on generations of traumatic experiences with outsiders.”

FUNAI, Brazil’s Indigenous affairs department, has documented evidence of these tribes through aerial surveys and careful monitoring, revealing communities that range from a few dozen to several hundred members. Their policy emphasizes protection without forced contact—a recognition of these tribes’ autonomy and right to self-determination.

Masters of Adaptation

Life in the Amazon demands extraordinary skill and resilience. The Awá, one of the groups with occasional outside contact, exemplify the nomadic lifestyle common among many uncontacted tribes. They construct temporary shelters from forest materials, able to move within hours if danger threatens.

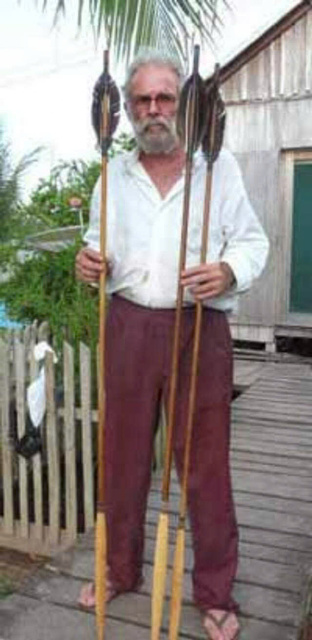

Their knowledge of the rainforest surpasses academic understanding—it’s lived experience, passed through generations. Giant bows over four meters long, discovered in abandoned camps, reveal sophisticated hunting techniques. Discarded tortoise shells tell stories of feasts and culinary preferences. Small forest clearings transformed into gardens showcase agricultural practices perfected over centuries.

“What outsiders might perceive as ‘simple’ existence is actually an intricate relationship with the ecosystem,” notes Dr. Elena Vargas, an ethnobotanist who studies Indigenous plant knowledge. “These communities understand sustainability not as a concept but as a way of life.”

Endangered Existence

Invisible Killers

For uncontacted tribes, the greatest threat often comes from what they cannot see: disease. Without immunity to common illnesses like influenza or measles, a single encounter with outsiders can devastate entire communities. The Matis people, who experienced contact in the 1970s, lost half their population within months—most tragically, the elders and shamans who carried their cultural knowledge.

This vulnerability makes protective isolation not merely a preference but a survival strategy. Medical anthropologists estimate that dozens of uncontacted groups have disappeared completely after contact-induced epidemics swept through their communities.

The Shrinking Forest

As the Amazon faces unprecedented deforestation, uncontacted tribes find themselves in an increasingly precarious position. Illegal logging operations, cattle ranching, mining, and infrastructure projects carve away at their territories, often with violent consequences.

The story of Karapiru, an Awá man who survived an attack by armed gunmen, illustrates this reality. After witnessing the massacre of his family, he lived alone in the forest for ten years before eventually reconnecting with other Awá communities. His death from COVID-19 in 2021 came as a bitter reminder of ongoing vulnerabilities.

Even more haunting is the fate of the “Man of the Hole” in Rondônia state, the last member of his tribe who lived alone for nearly three decades after ranchers killed his people. Known for digging deep holes in the forest floor—perhaps traps or hiding places—he rejected all contact efforts until his death in 2022, marking the extinction of an entire culture.

Race Against Time

The Piripkura and Kawahiva represent some of the most endangered uncontacted groups today. The Piripkura—nicknamed “butterfly people” for their constant movement—have dwindled to just a handful of known survivors. Emergency protection orders for their territory require constant renewal, creating precarious legal protection.

“The situation becomes more desperate each year,” says Indigenous rights advocate Maria Gonzalez. “Without permanent protection measures, we’re witnessing the slow erasure of irreplaceable human cultures.”

The Kawahiva face perhaps even greater challenges. Constant flight from intruders prevents them from maintaining permanent settlements or cultivating crops, forcing them into an increasingly unsustainable nomadic existence.

Guardians of Knowledge

Living Libraries

Each uncontacted tribe represents a living library of knowledge about the Amazon ecosystem. Their pharmacopeia includes plants unknown to modern medicine, their sustainable hunting practices maintain ecological balance, and their agricultural techniques preserve soil health without chemicals.

“When we lose an uncontacted tribe, we lose thousands of years of accumulated knowledge about the rainforest,” explains Dr. Carlos Mendes, a biologist specializing in Amazonian biodiversity. “Knowledge that could be crucial for addressing challenges like climate change and sustainable resource management.”

This perspective shifts the narrative around uncontacted tribes from one of primitive isolation to one of cultural wealth and ecological wisdom—communities that have maintained sustainable relationships with one of Earth’s most complex ecosystems for millennia.

Video

A Different Path

The existence of uncontacted tribes challenges conventional narratives about progress and civilization. They offer living proof that human societies can follow diverse paths of development while maintaining deep connections to the natural world.

“Their choice of isolation isn’t a rejection of advancement,” notes anthropologist Dr. Sarah Thompson. “It’s an embrace of a different kind of advancement—one that prioritizes ecological harmony, community bonds, and cultural continuity.”

A Fragile Future

The fate of Brazil’s uncontacted tribes hangs in delicate balance. International advocacy groups work alongside FUNAI to monitor territories and prevent invasions, but enforcement remains challenging in remote regions. Protection posts staffed by field officers serve as front-line defenses, but funding fluctuates with political winds.

Legal recognition of Indigenous territories provides some security, yet implementation often falters. Global awareness campaigns have helped pressure governments and corporations to respect these communities’ rights, but economic interests frequently override protection efforts.

The story of Brazil’s uncontacted tribes is still being written. Whether it ends with cultural extinction or renewed respect for their autonomy depends largely on choices made far from the forest—in government offices, corporate boardrooms, and international forums.

As the Amazon continues to face unprecedented threats, these communities stand as living testaments to human resilience and diversity. Their survival represents not just the persistence of unique cultures but also the preservation of alternative ways of understanding our relationship with the natural world—knowledge that may prove essential as humanity faces global environmental challenges.

In the shadowed depths of the Amazon, they remain—the keepers of ancient wisdom, the guardians of the forest, the embodiment of a different path forward.