In the heart of ancient Mesopotamia, where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers carved civilization into existence, stood magnificent palaces that would inspire awe for millennia. Among these architectural marvels, none were more imposing than the citadel of Sargon II at Khorsabad, where colossal sentinels stood eternal watch at the palace gates.

The Mighty Protectors of Khorsabad

Creatures of Divine Power

These guardians, known as Lamassu, were no ordinary statues. Standing up to 20 feet tall and weighing between 30 to 50 tons, these magnificent beings were carved from single slabs of limestone, gypsum alabaster, or breccia with extraordinary skill. Each Lamassu possessed the commanding presence of a divine protector – the wise, bearded face of a mature man crowned with the double horns of godhood, mounted upon the powerful winged body of a bull.

The artisans of Sargon II’s era, working between 720 and 705 B.C.E., created these masterpieces with meticulous attention to detail. The Lamassu’s broad face featured a strong nose and dramatically arched eyebrows that spanned the entire forehead. His massive beard, intricately curled and braided, nearly doubled the size of his visage, while his wide eyes gazed beyond the human realm into matters of cosmic significance.

The Crown of Divinity

Atop each guardian’s head sat a feather-topped crown adorned with rows of rosettes – symbols sacred to the goddess Ishtar and markers of divine authority. The double-horned crown proclaimed the Lamassu’s celestial nature, while pointed bovine ears, decorated with golden hoops and suspended beads, emerged from beneath flowing locks that cascaded into tight curls, creating an impression of ethereal movement.

The Art of Supernatural Movement

The Mystery of Five Legs

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of these guardians was their ingenious design featuring five legs instead of four. This architectural marvel served both practical and symbolic purposes. When approached from the front, the Lamassu appeared to stand in stoic vigilance, but as visitors passed between them, all four legs became visible, creating the illusion of forward movement.

This clever innovation addressed two critical needs: maintaining the structural integrity of the doorway arch by preserving the stone’s bulk, and ensuring that from any viewing angle, the Lamassu projected an image of formidable power. The massive, muscular legs conveyed the raw strength of these hybrid creatures, while their huge cloven feet anchored them firmly to their sacred duty.

A Canvas of Ancient Colors

Modern visitors see these sculptures in their natural stone hues, but in ancient times, they blazed with vibrant pigments. Archaeological analysis has revealed microscopic traces of white calcium carbonate and sulfate, bone black, charcoal, hematite red, cinnabar red, and cobalt blue that once brought these guardians to vivid life.

The Voice of the King

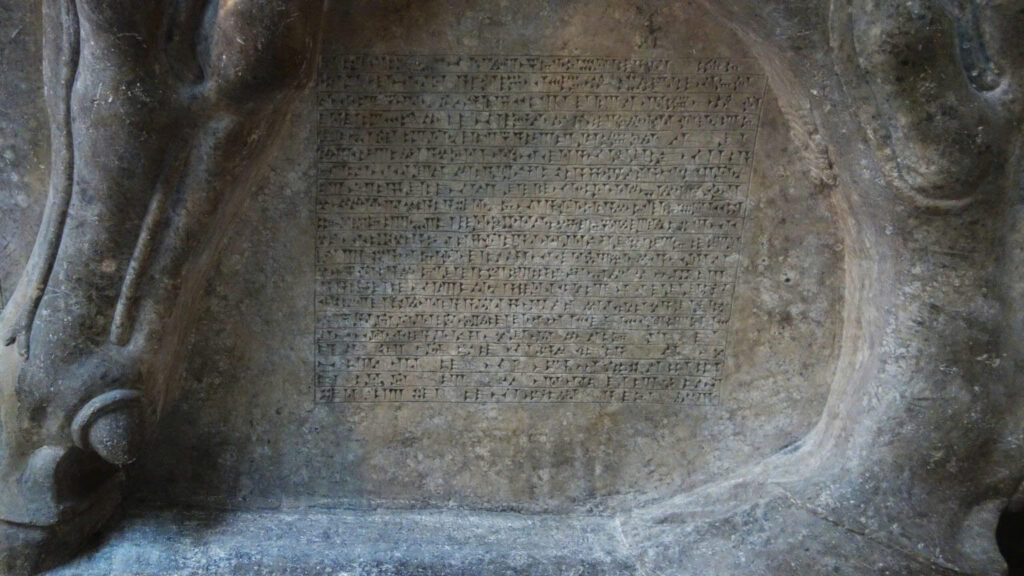

Sacred Inscriptions

Between the hind legs of each Lamassu, cuneiform inscriptions told the story of King Sargon’s triumphs and divine favor. These standard inscriptions served as both proclamation and protection, listing the monarch’s victories and virtues while invoking curses upon any who would dare harm his palace. The text represented a scriptural layer beneath the visual narrative, reinforcing the power and legitimacy of Assyrian rule.

Masters of Precision

The Artisan’s Triumph

What strikes modern observers most profoundly about these sculptures is not merely their imposing size, but the extraordinary precision of their execution. In an era centuries before mechanical reproduction, craftsmen achieved scrupulous and endlessly repetitive perfection in every curl, horn, feather, and rosette. The strict mathematical arrangement of decorative elements created a sense of controlled power, humanizing the potentially chaotic nature of these hybrid beings through masterful restraint.

The deep, powerful cuts in high relief and the sharp readability of every detail demonstrate the supreme skill of Neo-Assyrian sculptors. This terrifying precision in sculptural repetition across multiple figures speaks to a level of craftsmanship that commands respect even today.

Video

A Legacy Under Threat

From Palace Gates to Museum Halls

Today, these ancient guardians stand in museums around the world – the Louvre, British Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad. They arrived at these institutions through 19th-century archaeological expeditions that brought them from their original homes in modern-day Iraq.

Yet many Lamassu remained at their original posts, continuing their millennia-old vigil at archaeological sites throughout Iraq. Among these were the guardians of the Nergal gate at ancient Nineveh, built during Sennacherib’s reign around 700 B.C.E. to honor Nergal, the Assyrian god of war and plague who ruled the underworld.

The Tragedy of 2015

In 2015, the world watched in horror as ISIS militants destroyed these irreplaceable guardians at the Nergal gate and in the Mosul museum. Using jackhammers, drills, and sledgehammers, they demolished these ancient protectors, claiming they were “idols” that needed to be destroyed. This act of cultural vandalism represented not just the loss of priceless artifacts, but the severing of humanity’s connection to its ancient heritage.

The Eternal Watch

Though some of these magnificent guardians have been lost forever, their legacy endures. The surviving Lamassu continue to inspire awe and wonder, their presence echoing across millennia to remind us of the power of human creativity and the enduring strength of cultural memory. They stand as testament to the Neo-Assyrian Empire’s artistic achievements and as eternal guardians of our shared human heritage.

In their museum homes around the world, these ancient sentinels continue their watch, no longer protecting palace gates but serving as bridges between our modern world and the magnificent civilization that created them. Their story reminds us that some guardians transcend time itself, carrying the weight of history in their stone forms and the dreams of eternity in their steady gaze.