In the ancient land of Assyria, where paranoia and power walked hand in hand, there lived a king who would become legendary not for his conquests alone, but for his relentless war against the forces of disorder. This is the story of Ashurbanipal, the third son who was never meant to rule, yet became one of history’s most fascinating monarchs.

The Ritual of Royal Deception

The Assyrian kings lived in constant fear of omens and threats. When danger loomed, they practiced a bizarre ritual of royal substitution. The true king would vanish, disguising himself as a humble farmer, while a replacement—perhaps a loyal servant, a political enemy, or even a court fool—would assume the throne. This false monarch would rule for up to 100 days, complete with a queen by his side, before being executed and granted a royal burial once the peril passed. Through this macabre theater, the Assyrians believed they could outwit fate itself.

Ashurbanipal’s father, the deeply paranoid Esarhaddon, is believed to have performed this deadly masquerade at least three times, a testament to the perpetual anxiety that plagued the Assyrian crown.

The Unexpected Heir’s Rise to Power

Ashurbanipal was not destined for kingship. As the third son, the throne seemed far from his reach. Yet through the shrewd maneuvering of the powerful queen mother, he ascended to rule one of the ancient world’s mightiest empires from 669 to 631 BC. His reign would span nearly four decades of brutal magnificence.

The Endless Hunt: Lions as Symbols of Chaos

The Royal Hunt as Sacred Duty

For Ashurbanipal, slaying lions was far more than sport—it was a sacred obligation. The palace walls at Nineveh bore witness to this eternal struggle through magnificent gypsum carvings that depicted the royal hunt. These weren’t mere decorations but visual narratives of a king’s perpetual battle against disorder.

The carved scenes read like a recurring nightmare: a child releases a lion from its cage, and the same king repeatedly battles the same beast with arrows, swords, and spears. This cyclical imagery revealed a profound truth—the work of taming chaos is never truly finished.

Artistry Born from Violence

The Assyrian craftsmen possessed an extraordinary ability to translate the textures of their world into stone. Every detail was meticulously carved: the flowing curves of a horse’s tail, the tension in a warrior’s calf muscle, the intricate weave of fabric. Even mundane elements like door thresholds were transformed into works of art, carved with rosettes and tassels that mimicked the carpets they replaced.

The artists observed animal suffering with unsettling intensity, capturing every rivulet of blood where weapon met flesh. Yet human anguish remained a delicate subject for official art, leading to subtle expressions of individual pain within formal compositions. Disgraced guards would kneel in empty space, suspended like fallen angels.

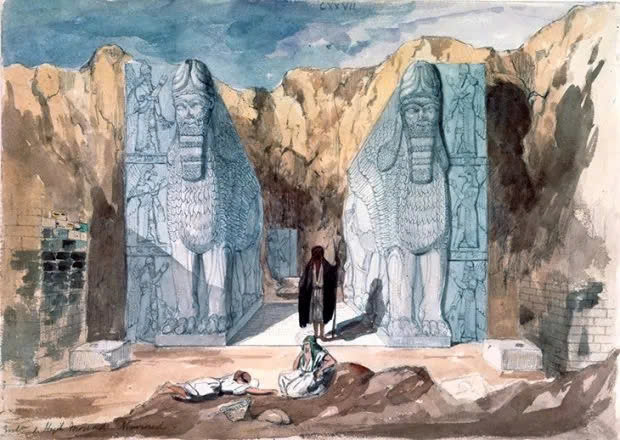

The Darkness at the Palace Gates

Family Betrayal and Magical Protection

Ashurbanipal’s fears were grounded in harsh reality. Violence ran in the royal bloodline—his grandfather had been murdered by his own son. Now the king faced treachery from his older brother, who had been appeased with the vassal kingdom of Babylonia but secretly plotted rebellion.

Understanding the danger of thresholds and transitions, the palace doorways were guarded by protective spirits carved in low relief: bearded figures in kilts and eagle-footed beings wielding daggers. Palace scholars carefully planned these magical defenses, consulting sheep entrails to divine approaching threats.

The Scholar-King’s Pursuit of Knowledge

From Spymaster to Librarian

Before becoming king, Ashurbanipal had served as his father’s spymaster, gathering intelligence on Assyria’s enemies. This hunger for information never left him. As ruler, he was often depicted with a stylus tucked in his belt—a symbol of his intellectual pursuits.

The library he assembled became one of the ancient world’s greatest repositories of knowledge, preserving for posterity the epic of Gilgamesh among countless other works. Yet this collection reflected the king’s primary concern: understanding divine will rather than entertainment. Tablets devoted to interpreting abnormal birth omens outnumbered creation stories by more than three to one.

The Network of Knowledge

The library’s contents came from two sources: original works created in the palace (sometimes by captive scribes working in chains) and texts plundered from conquered territories. A sophisticated messenger relay system ensured rapid communication across the empire, spreading not only information but artistic styles and cultural ideas.

The Empire’s Reach and Influence

Cultural Exchange Through Conquest

Assyrian influence extended far beyond military conquest. The lotus and bud motif traveled from Egypt, while griffin designs appeared simultaneously on Cypriot cauldron rims, Turkish bronze fittings, and Iranian glazed tiles. Client states transformed their economies to feed Assyria’s appetite for raw materials and luxury goods.

Egyptian obelisks were melted down to decorate Assyrian temples, while tribute payments encouraged Phoenician port cities to become centers of luxury craftsmanship. An exquisite ivory panel found at Nimrud—depicting a lioness devouring a young man, inlaid with carnelian and lapis lazuli—exemplifies the sophisticated artistry that tribute demands fostered.

The Beautiful Horror of War

Art as Propaganda and Poetry

The carved panel depicting the Battle of Til-Tuba represents the pinnacle of Assyrian war art. This hellscape shows Ashurbanipal’s forces crushing the Elamite army and returning with their king’s severed head. Ordered battle formations dissolve into chaos as warriors tumble into rivers where fish nibble at their quivers.

The artists abandoned their typical impassive, hieroglyphic style for something more disturbing—a sophisticated portrayal of suffering that makes beauty inseparable from violence. These works served as both propaganda and artistic achievement, demonstrating how power and aesthetics intertwined in ancient Assyria.

Video

The Fall and Ironic Justice

When the Mighty Became Victims

In 612 BC, Nineveh fell to the combined forces of Babylonians and Medes. The triumphalist artworks that had celebrated Assyrian invincibility became casualties of war. In one of history’s poetic ironies, a hunt scene that showed the king grasping a lion by the tail, ready to deliver the killing blow, was itself damaged when the palaces were looted.

Vandals defaced the king’s raised arm and chipped away at the lion’s tail, effectively “liberating” the stone beast. An image designed to showcase eternal power became instead a testament to the fragility of all earthly dominion.

The Modern Discovery and Its Consequences

Archaeological Adventure and Imperial Collection

The excavation of Nineveh began in the 1840s under Austen Henry Layard and continued with Hormuzd Rassam, an Assyrian Christian from Mosul. Working by moonlight to avoid French competitors, Rassam discovered many of the lion panels that now reside in London.

As he wrote, “In my position as agent of the British Museum, I had secured it for England.” Nearly all sculptures were transported on rafts down to Basra, then shipped to London. This history of acquisition—how these treasures flowed from the Tigris to the Thames—remains largely unexamined in modern museum displays.

The Eternal Lesson

The story of Ashurbanipal and his lion hunts reveals timeless truths about power, art, and human nature. His obsessive battle against chaos, captured in stone by master craftsmen, continues to speak across millennia. In those carved panels, we see not just an ancient king’s propaganda, but humanity’s eternal struggle against the forces that threaten to overwhelm order and civilization.

The lions may be long extinct, the palace walls may have crumbled, and the king himself may be dust, but the story carved in stone endures—a reminder that the battle against chaos, in all its forms, remains humanity’s most persistent challenge.